No products in the cart.

Knowing the backstories behind the makers, however, adds to the pieces’ allure. Below we share the histories and most beloved patterns of five venerable potteries, most of which are still producing exquisite wares today.

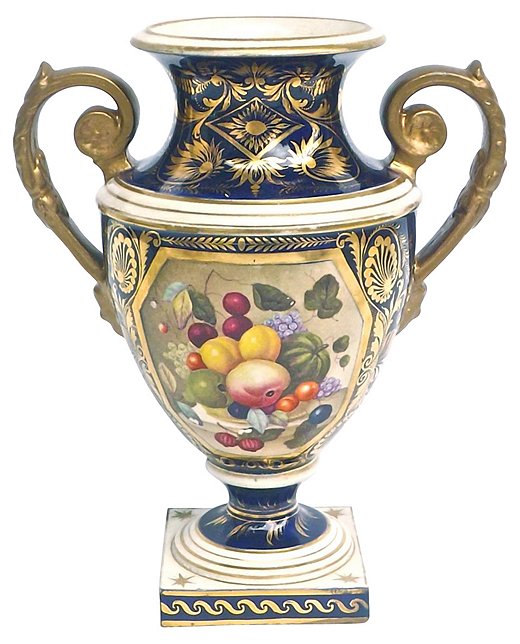

A bit of history: Royal Crown Derby claims to be the oldest English porcelain maker still in operation (though rival Royal Worcester also makes that claim). What isn’t in dispute is that the company was selling porcelain tableware, vases, and figurines in the early 1750s. At that time it was known as Derby Porcelain Company; not until 1775 did King George III allow the manufacturer to incorporate a crown into its maker’s mark, enabling it to add Crown to its name (and making it easier to determine whether a piece was produced prior to then). The company’s name changed once again in 1890, when Queen Victoria granted it a royal warrant and the addition of Royal to its name.

Royal Crown Derby

Notable designs: Beginning in the early 1800s, Crown Derby began producing tableware and decorative pieces inspired by Imari ware, a type of vividly colored porcelain from Japan. One of its earliest such patterns, the lavishly adorned Old Imari bone china, is still handcrafted today. The floral Imari Accent pattern is new in comparison, having been introduced in the early 20th century.

Fun fact: While most of the longstanding English pottery makers set up shop in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire—which led the town to become known as the Potteries—Royal Crown Derby was based in (no surprise here) Derby.

Wedgwood

A bit of history: Josiah Wedgwood launched his eponymous firm in 1759 with the invention of a green glaze. Yet today his company is best known for unglazed jasperware and Wedgwood blue. Those were just two of Wedgwood’s innovations. Sometimes called the Father of English Potters, Wedgwood also invented the pyrometer, a tool to measure the extremely high temperatures in his kilns, and is credited with numerous marketing innovations, such as illustrated mail-order catalogs, money-back guarantees, and buy-one-get-one-free promotions.

Notable designs: Wedgwood’s refinement of cream-colored stoneware with a fine off-white glaze was so spectacular in its day that Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, commissioned a large order in 1765 and allowed Wedgwood to call it Queen’s Ware, which boosted his company’s popularity with the nobility. At the same time, because it was more affordable than porcelain and china it was sought-after by the middle classes as well.

Another royal, Russia’s Catherine the Great, commissioned a type of Queen’s Ware boasting hand-painted bucolic scenes with a frog in a shield featured along the border. Most of the original 944 pieces of her Frog Service are on display in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage museum.

Jasperware is notable for its matte finish and the white cameolike reliefs placed on top. The skylike shade known as Wedgwood Blue remains the most popular, but it has been made in several dozen other colors as well. Also matte is Black Basalt, or basalt ware, an improvement on the Egyptian black stoneware of the mid-1700s; Wedgwood used it primarily for classical vases and urns, sometimes pairing it with a reddish stoneware he dubbed Rosso Antico.

Not all of Wedgwood’s most in-demand designs date back to Josiah’s era. Launched in 1915, Fairytale Lustre was produced for only 14 years, but it was wildly popular then and remains so today. Designed by Daisy Makeig-Jones, it is almost the antithesis of what we think of as typical Wedgwood. Each brilliantly glazed piece boasts highly detailed Art Nouveau-inspired fantasy vignettes.

Fun facts:Â Josiah Wedgwood was a grandfather of Charles Darwin. And poet/artist/mystic William Blake worked as an engraver for the Wedgwood catalogs in 1815.

A bit of history: England, of course, doesn’t have a monopoly on fine tableware. For instance, Italian marquis Carlo Ginori was so taken with porcelain tableware, in 1735 he founded a manufacturing factory near his villa in Doccia, outside Florence. Ginori’s first creations were porcelain reproductions of classical statues and renditions of models and casts from some of the top sculptors of the day. The company merged with Milan’s Socièta Richard in 1896 and was bought out of bankruptcy by Gucci in 2013. In between, in 1923, it named innovative architect/furniture designer/artist Giò Ponti its creative director, a position he held for 10 years.

Notable designs: Ponti’s first collection for Richard Ginori, Le Mie Donne, imbues classical motifs such as Greek statuary and Ionic columns with an Art Deco sleekness and a glossy enamel finish. Oriente Italiano, Ponti’s interpretation of chinoiserie, is available in 10 colorways, from staid black-on-white to vivacious blue-on-pink.

Richard Ginori

Harking back to an earlier time, Primavera features delicate blossoms and gold trim against scalloped and fluted white porcelain. Another floral pattern, Granduca Coreana, debuted in 1750 under the auspices of founder Carlo Ginori and is still produced today.

Fun facts: The Medici family collected Ginori porcelain, and the company created a massive service for Napoleon’s second wife, Marie Louise of Austria.

A bit of history: Wedgwood and Spode still produce new designs and reiterations of its classics. Another of the original Stoke-on-Trent potteries, Mintons, ceased production in 2005. Thomas Minton founded the firm in 1793, and at first it specialized in blue-and-white transferware, with its version of the chinoiserie-influenced Willow pattern becoming a best-seller. By the middle of the 19th century, however, Mintons was becoming better known for its innovations in majolica and Palissy ware. (Technically majolica uses a tin-based glaze while Palissy ware uses a lead-based one, but by the end of the Victorian era both were called majolica.) Equally acclaimed was its Parian ware, a type of porcelain that mimicked marble but was much more affordable.

Â

MINTONS

Notable designs: As its name indicates, Mintons’ Renaissance majolica took inspiration from Italian Renaissance themes, but it added a profusion of ornamentation, colors, and gilt to satisfy Victorian tastes. Also in high demand among collectors is its Secessionist Ware, inspired by the Viennese Secession, an Art Nouveau movement of the turn of the 20th century spearheaded by, among others, artist Gustav Klimt. These earthenware items were simpler in form than Mintons’ lavish majolica, with nature-inspired motifs ranging from realistic to highly stylized.

Fun fact: Queen Victoria paid the modern-day equivalent of around $170,000 for a Mintons dessert service that she gave to Franz Joseph I of Austria.

SPODE

A bit of history: Another 18th-century English potter named Josiah who set up shop in Stoke-on-Trent came up with a few innovations of his own. Around 1784, Josiah Spode I refined a method of transfer printing on earthenware—itself developed in the 1750s—that allowed a glaze to go on top of the design while enhancing the color and the image. This underglaze blue transfer printing led Spode’s company to take the lead in mass-producing dishware with fine designs that appeared to be hand-painted. He also developed a formula for bone china that, after additional refinements by his son, Josiah Spode II, remains the standard today. In 1833, after the death of Josiah II, William Tayler Copeland (with, for a period, Thomas Garrett) took over the company, which is why wares sometimes bear the marks of Copeland & Garrett, Copeland, Copeland & Sons, or Copeland Spode.

Â

Notable designs: Spode produced hundreds of patterns of blue-and-white transferware, but Blue Italian is its most famous and enduring: Introduced in 1816, it is still in production today. While the chinoiserie influence is apparent, particular in the border designs, the central images of the pieces are, as evidenced by the line’s name, Italian landscapes.

Predating Blue Italian by two years and in production through the 1960s, the Cabbage pattern (also known as Tobacco Leaf) was a colorful interpretation of a Chinese design, featuring cobalt-blue and red leaves, multicolored flowers, and bamboo stalks with gold accents. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright ordered a set for his own home.

For many families, especially in the South, it just isn’t Christmas without Spode’s Christmas Tree dishware on the table. The pattern debuted in 1938, and Spode continues to issue versions of it.

Fun fact: William Tayler Copeland was Lord Mayor of London from 1835 through 1836.